That Notorious Broadcast: Panic, Propaganda, and the Power of Radio

It’s 8 p.m. on October 30, 1938. In Studio One, on the 20th floor of the Columbia Broadcasting Service in New York City, history is about to be made.

At the podium stands Orson Welles, alongside 10 actors and a 27-piece orchestra. It’s Halloween Eve – aka Mischief Night, Devil’s Night, Hell Night – a night known for centuries to unleash all manner of trickery on the unsuspecting. Tonight will be no exception.

The first words crackle over the airwaves loud and clear:

“The Columbia Broadcasting System and its affiliated stations present Orson Welles and the Mercury Theatre on the Air in The War of the Worlds by H.G. Wells.”

That 10-second disclaimer might have been the only clue listeners had—if they tuned in on time. But many didn’t. Within minutes, the nation was gripped by what appeared to be a real Martian invasion. Legendary chaos ensued… but did it?

This is the story of the 1938 War of the Worlds broadcast—one of the most infamous media events in American history—and the myths and truths it left behind.

Estimated reading time: 20 minutes

Who’s Who Here?

First, let’s clear something up, as there can be confusion on this point:

H.G. Wells is the author of the original book The War of the Worlds, published in 1898. A prolific science fiction pioneer, he also gave us classics like The Time Machine and The Invisible Man.

Orson Welles (note the extra ‘e’) is the legendary actor/director who adapted the book into the now-infamous radio broadcast 40 years later.

Now that we’re clear on which Well(e)s did what, let’s dive into the broadcast itself.

Setting the Stage: 1938 America

The broadcast aired during a period of global unease:

- The Great Depression had left emotional and economic scars.

- The Munich Crisis had just occurred a month earlier.

- Hitler’s rise in Europe had Americans on edge.

- The Hindenburg disaster (May 6, 1937) and other real-time radio reports conditioned listeners to expect sudden, terrifying news bulletins.

It was the perfect environment for confusion—and perhaps panic. Add to that the ever-increasing interest in Mars itself…

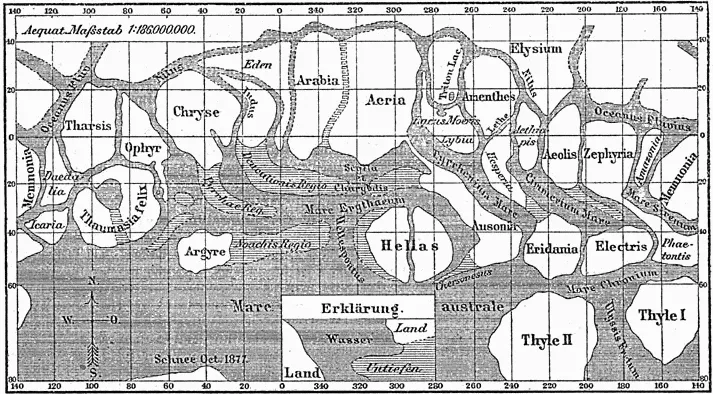

Canal confusion – In the late 1800s, astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli documented the now well-known striations across the red planet. However, the Italian word for “channels” was mistranslated to English as “canals.” The 19th century a canal-building era, for listeners of the day the word “canal” suggested engineering—leading to speculation about intelligent life on Mars.

Further speculation – American astronomer Percival Lowell was a strong proponent of the idea of Martian canals. He first detailed his observations and interpretations in his 1906 book, Mars and Its Canals. He then further developed this concept in his 1908 book, Mars as the Abode of Life, proposing that a Martian civilization had constructed these “canals” as a vast irrigation system to transport water from the polar ice caps to the equatorial regions.

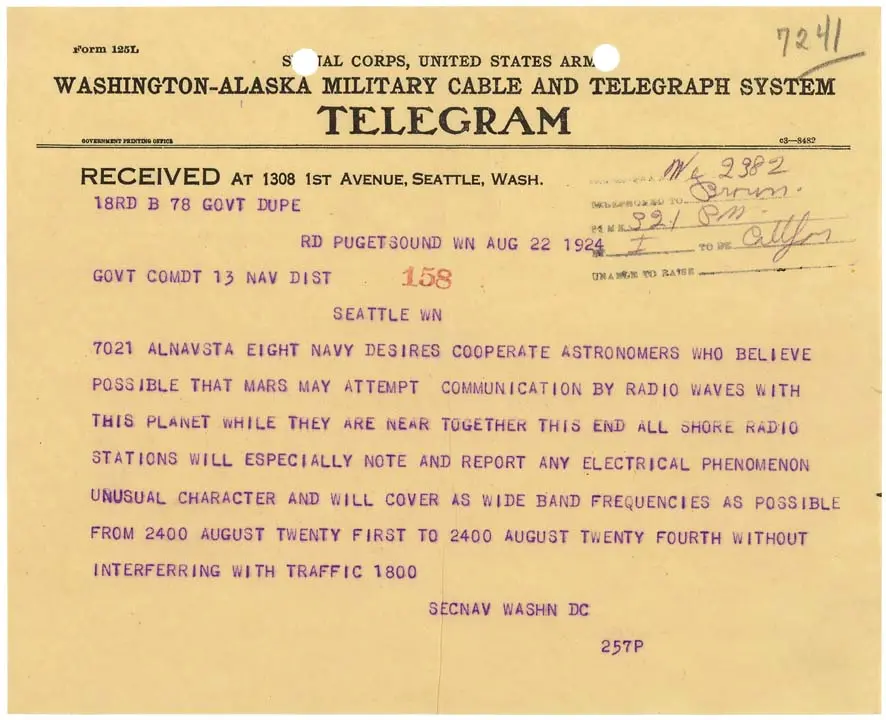

Listening in – In August 1924, during a period of opposition with the red planet, the U.S. Army Signal Corps asked radio stations nationwide to shut down so that its engineers could listen for signals from Mars.

Life on Mars – The public’s fascination with Mars continued to grow in the days leading up to the broadcast. On October 27, 1938, the Christian Science Monitor published an article featuring Swedish astronomer Knut Lundmark, who speculated that “living things exist not only on Mars but also upon some of the other planets.” This piece, appearing just three days before the broadcast, likely amplified public curiosity about extraterrestrial life, making Welles’ fictional Martian invasion all the more believable to some listeners.

The Broadcast Itself: Realism by Design

Orson Welles, only 23 years old, and the Mercury Theatre on the Air adapted H.G. Wells’ 1898 novel into a radio play styled as a series of live news bulletins. Here’s how the two versions differ (click arrow to reveal details)…

H.G. Wells’ Original Novel

- Narrated as a first-person account by an unnamed protagonist, with a parallel story from his brother

- Set in Victorian-era England, specifically around London and Surrey

- Told as a historical account of events that had already happened

- Detailed descriptions of the Martians and their technology, including the iconic tripods

Orson Welles’ Broadcast

- Presented as breaking news bulletins and live reports

- Relocated to New Jersey and New York, specifically starting in Grover’s Mill, NJ (a location randomly chosen on a map)

- Broadcast as if happening in real-time

- Used familiar radio formats: news breaks, interviews, remote reporters, and “expert” commentary

The broadcast’s genius lay in its format. After the introduction, Welles presents a seemingly ordinary evening of radio programming, beginning with weather reports and dance music. Then, around the 3½-minute mark, comes the first “interruption:” a news bulletin about strange observations from Mars.

From there, the broadcast escalates into a full-scale alien invasion narrative, told entirely through news reports, interviews, and on-the-scene coverage – all with NO commercial breaks!

Famously, many listeners missed the intro. Why? Because apparently the most interesting thing on the airwaves that night was a ventriloquist act. On the radio. Think about that for a second.

Nevertheless, of the millions of American listeners that Sunday evening, most were not tuned to CBS, but to NBC, for the hit variety show The Chase & Sandborn Hour – featuring Edgar Bergen and his wooden dummy Charlie McCarthy.

But, as was typical in those days, at the first musical interlude the dial-twisting (radio version of channel surfing) began. Listeners who missed the intro to War of the Worlds were thrown into a chilling “live” report of an alien invasion.

How Real Was It?

According to the PBS documentary American Experience: War of the Worlds, a busy Orson Welles was not heavily involved in the creation of the broadcast until frightfully close to the air date. At that time, he found the current version of the radio play drab and boring.

Enter inspiration… Just days before the broadcast, Welles happened to hear a CBS broadcast of a play entitled Air Raid, by Archibald MacLeish. A fictional story, the form mimicked the style of a breaking news flash. The War of the Worlds script was hastily rewritten in the new format.

Actor Frank Readick, cast to play on-the-spot reporter Carl Phillips, found inspiration in the CBS record library, where he repeatedly listened to Herb Morrison’s eyewitness account of the Hindenburg disaster. Notably, this disaster took place in New Jersey—the same setting as the radio play’s Martian invasion.

Adding to the realism, actor Kenneth Delmar crafted a near-perfect impersonation of Franklin D. Roosevelt, mimicking the President’s mannerisms and speech patterns. Although the character was clearly identified as “the Secretary of the Interior,” Delmar’s spot-on impression left its mark, as many anxious listeners believed they heard the President speaking.

Mid-way through Delmar’s speech, according to the PBS documentary, a telephone rang in the control room. The CBS supervisor who hurried out of the studio to take the call returned moments later looking “pale as death.” CBS switchboards were overwhelmed. Network executives demanded an identifying station break immediately.

But Welles was in the zone and didn’t deliver the announcement until 42 minutes past the hour – 10 minutes after CBS’s demand!

By this point, many listeners were already caught up in the panic—a testament to how convincing the first half-hour had been. Those who had been genuinely frightened had likely already called the police, woken up their neighbors, or even fled their homes before these later disclaimers aired.

All in all, the broadcast is true to the book. The main changes are the setting and the storytelling method. It’s possible American audiences of the day were not well familiar with the material. Or, if they were, perhaps they feared H.G.’s speculative science fiction had become prophetic.

It should be noted that not all who reacted with fear were convinced of an extraterrestrial attack. With World War II looming in Europe, some people misunderstood “alien invasion” to mean an attack by Hitler’s Germany. Those who were not listening closely could easily jump to this conclusion.

The Panic: What Really Happened?

The panic that followed has become legendary, though modern historians suggest it wasn’t as widespread as initially reported. Fifteen minutes into the broadcast, switchboards lit up across the country.

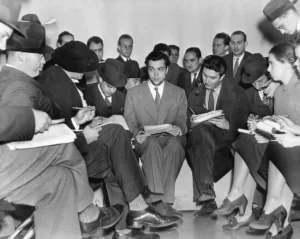

According to Media Historian Paul Heyer, police and news reporters flooded the studio immediately after the broadcast, cornering Welles and co-producer John Houseman, and playing up the severity of the public reaction.

The pair were then rushed downstairs and sequestered while network employees collected, destroyed, or locked up all scripts and records of the broadcast.

By the following morning, news of the broadcast was nationwide. Reports of near-riots, traffic accidents, and hordes of panicked masses peppered the headlines.

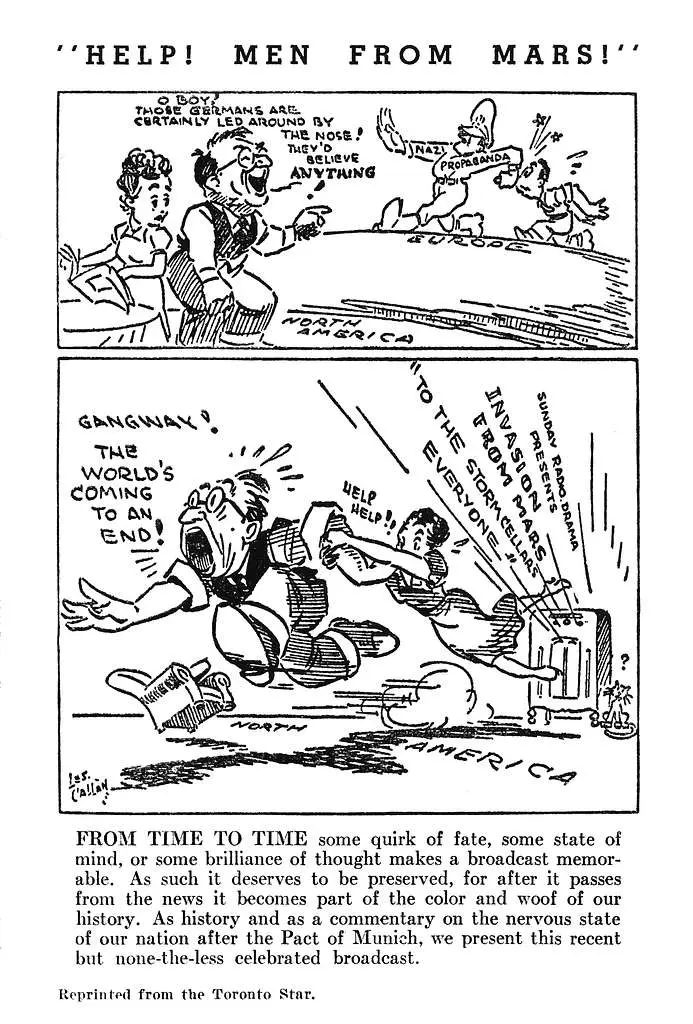

But later analysis—including by sociologists and historians—found the scale of the panic was heavily exaggerated by newspapers. Why?

- Newspapers were threatened by the growing popularity of radio

- They saw an opportunity to discredit the medium by portraying it as dangerous

In truth, only a small percentage of the radio audience was actually listening to War of the Worlds that night. And even fewer panicked.

Nevertheless, the radio play was now cemented in history as the “panic broadcast.”

Was the Panic Only in the Northeast?

Nope! All the way across the country, in the tiny town of Concrete, Washington, it was an ominously stormy Halloween Eve. Radio was the only form of entertainment on a night like this, listeners who tuned in to the War of the Worlds broadcast may or may not have believed the events were real—until arguably the worst-timed coincidence in history.

Valerie Stafford, Concrete’s longtime Chamber of Commerce president, states in an interview:

“Here in Concrete, the Mercury Theater radio show came on at around 5 p.m., and people were listening to Orson Welles describing an alien invasion. Our phone service at that time was sketchy at best, so folks weren’t able to get outside confirmation of the hoax. What happened instead was frightening. At the point in the broadcast when Welles was announcing the landing of the Martians and a resulting power outage—at that very moment the power went out in Concrete.”

Stafford continues:

“…there was a sudden exodus of men who headed up into the hills to protect their moonshine stills. The sheriff eventually had to go up and reassure some of them that they and their hooch were safe.”

The town still commemorates the event with an annual cinematic tribute to War of the Worlds.

The Fallout

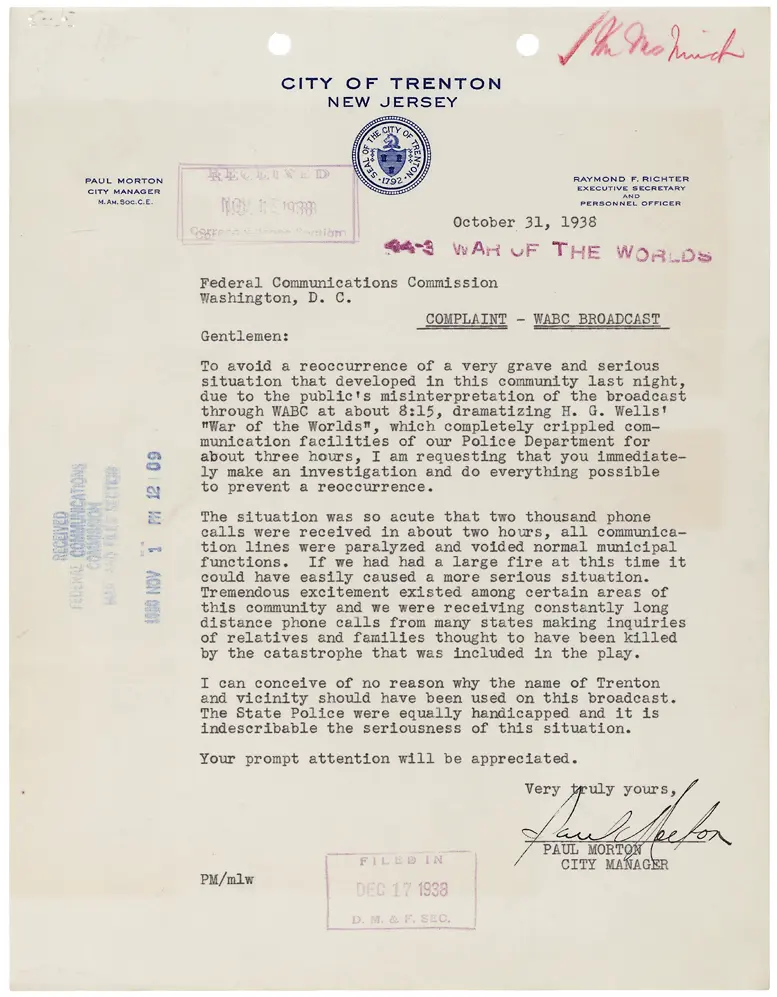

In the days following the broadcast, Iowa Senator Clyde Herring called for legislation to create a national board of radio censors. The Chief of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) ordered an investigation into CBS’s conduct. And CBS began to receive scores of outraged complaints and lawsuit threats.

Thousands of Americans wrote letters to the FCC, CBS, and Welles himself. These letters range from praise and admiration to bitter condemnation and disgust. A fascinating read, the letters are curated into a digital collection by the University of Michigan Library.

Many were more upset about the ridiculous reaction and what it revealed about the American people than about the broadcast itself. This complaint was echoed by editorial pages for the next two weeks, totaling over 12,500 newspaper articles.

People were very concerned about how easily propaganda could influence the masses, and felt safeguards should be put in place against it.

Hitler himself is reported to have mentioned the broadcast in his November 8th speech, using it to demonstrate “the corrupt condition and decadent state of affairs in democracy.”

The Princeton Study: Birth of Media Panic Research

In the weeks following the broadcast, a team at Princeton University sprang into action to understand what had just happened—and why. Led by psychologist Hadley Cantril, the study would become the very first scientific investigation into the power of mass media to influence public behavior.

Turns out, they were already preparing for something like this.

💡 Did You Know?

The Princeton study was already in progress before the 1938 broadcast! Funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, it became the first scientific analysis of mass media-induced panic.

With a $67,000 grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, Cantril had spent the past year designing tools to study radio’s impact—not just what people listened to, but why. The goal? To understand how broadcast media could shape beliefs, behaviors, and even national moods.

The War of the Worlds panic gave them the perfect test case.

Working independently from the radio industry (which had its own reasons to downplay any problems), the Princeton group launched interviews, surveys, and field reports almost immediately. Their findings were published two years later in Cantril’s landmark book, The Invasion from Mars: A Study in the Psychology of Panic (1940)—still cited today in media ethics, behavioral science, and communication studies.

The big takeaway? Many listeners didn’t blindly believe Martians had landed—but they did believe something terrible was happening. The broadcast didn’t just spark chaos—it exposed the thin line between media and mass delusion.

For the extra curious: you can browse the original Rockefeller Foundation grant records and research files here.

Dorothy Thompson’s Take: Media, Mass Delusion, and Democracy

Columnist Dorothy Thompson responded shortly after the broadcast—not to blame the show, but to raise deeper concerns:

The real issue wasn’t the show—it was how easily people were manipulated.

She warned of:

- The danger of persuasive leaders who play on fear and emotion

- The risks of too much media control in too few hands

- How easily this kind of mass reaction could pave the way for dictators, as it had in Europe

Her 1938 essay “Mr. Welles and Mass Delusion“ remains one of the most thoughtful responses to the broadcast’s legacy.

However, the FCC concluded its investigation just five weeks after the broadcast, on December 5, taking no punitive action against CBS. CBS had already voluntarily promised to avoid use of dramatized, simulated newscasts in the future. Furthermore, of the many lawsuits brought against Welles and CBS, none resulted in payment of damages.

Orson Welles: From Controversy to Icon

In the wee hours following the uproarious broadcast, CBS execs hastily convened a press conference. Orson Welles, the picture of innocence and remorse, issued his most sincere-sounding apology.

However, the broadcast catapulted Welles from local stardom to international fame overnight. Mercury Theatre landed its first sponsor, Campbell’s Soup. And Welles landed an unprecedented deal with RKO Studios: to write, produce, direct, and star in one film per year.

According to Welles’ daughter, Chris Welles Feder, initially Hollywood wanted Welles to replicate the War of the Worlds broadcast as a movie. But he wanted to do something new and fresh instead. This is how the groundbreaking Citizen Kane came into being in 1941.

Welles’ co-creators, producer John Houseman and writer Howard Koch, also went on to find acclaim. Houseman enjoyed a successful career, first as a producer then an actor, winning an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal of Professor Charles W. Kingsfield Jr. in the 1973 film The Paper Chase. Howard Koch co-wrote the 1943 film classic, Casablanca, securing his own Academy Award.

Years later, Welles admitted that the radio broadcast was “not as innocent” as he initially conveyed it to be, but rather an experiment on the power of radio and a critique of media trust.

Wells Meets Welles

“The best thing that has happened so far is meeting my little namesake here, Orson. I find him the most delightful carrier—he carries my name and an extra ‘e’ that I hope he’ll drop sooner or later.”

H.G. Wells

So, what was original author H.G. Wells thinking about all this? According to H.G. Wells and the War of the Worlds: A Documentary, his initial reaction mirrored the public attitude.

Concerned that people thought he’d been in on the hoax, Wells allegedly considered legal action at first. He stated that he only authorized the use of his novel because he thought it was going to be a broadcast reading, not a dramatized event. Fortunately for him, the hysteria faded quickly due to news of the actual war pervading the headlines.

In 1940, the two Wells(es) met on a radio program. Soothed by time and increased book sales, the British author was amused by the whole affair:

“Are you sure there was such a panic in America? Or wasn’t it your Halloween fun?”

They discussed the incident warmly, with H.G. noting Americans hadn’t yet experienced war firsthand and could afford to “play with ideas of terror.”

The 8 minute clip above focuses primarily on the radio broadcast. If you’re hardcore and need more, here’s the full 25 minute interview.

Fact vs. Fiction: What Really Happened?

Did people panic in the streets? Yes—and no.

- Switchboards lit up across the country

- Police showed up at CBS unsure what was happening

- Some listeners packed cars, called loved ones to say goodbye, or fled homes

| Myth | Reality |

|---|---|

| Millions panicked | Some localized confusion |

| People died | No confirmed panic-related deaths |

| Welles was arrested | Nope — he was swarmed by reporters and questioned by police, but never arrested. |

| FCC punished CBS | Investigation only; no penalties |

| CBS continued using fake news-style broadcasts | CBS promised to stop dramatized news bulletins after public and FCC pressure |

While the panic may not have been as widespread as legend suggests, the aftermath was very real. It reshaped broadcast policy, spooked networks into self-censorship, and forever blurred the line between fiction and reality in the public imagination.

The truth? The panic was real—but scattered, exaggerated, and shaped more by headlines than actual hysteria. The idea of the panic may have caused more disruption than the broadcast itself.

International Repeats: The Hoax That Traveled

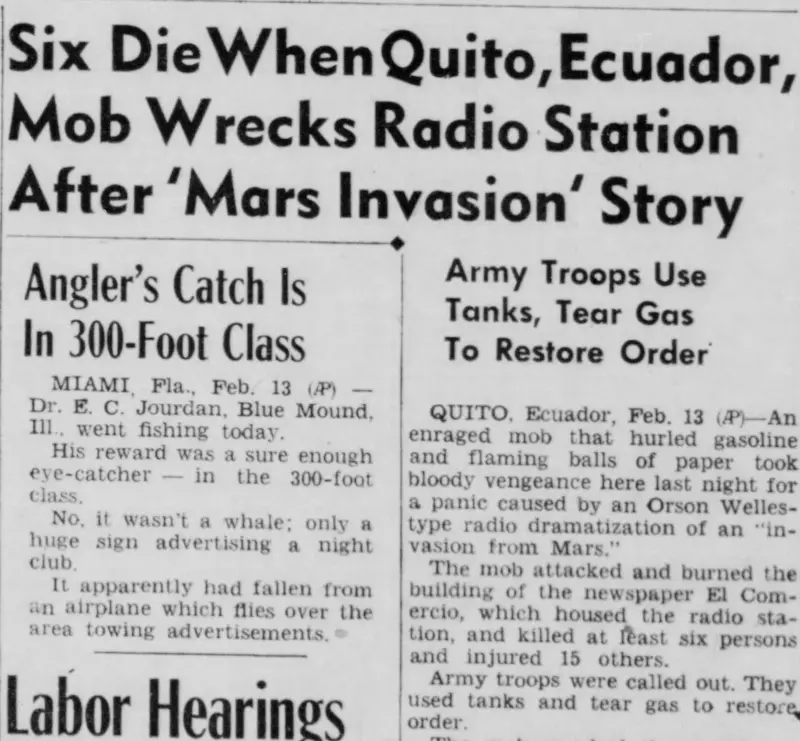

The 1938 broadcast’s influence didn’t stop at America’s borders. In the years that followed, countries around the world recreated the stunt—with some taking a far darker turn.

Two of the most dramatic international re-creations took place in South America:

- 1944, Santiago, Chile: On November 12, a radio dramatization by Radio Cooperativa Vitalicia sparked widespread panic across Santiago. Modeled after Welles’ 1938 broadcast, the program used realistic news bulletins and local references, reporting a Martian landing near Puente Alto. Although it was introduced as a fictional performance, many listeners missed the disclaimer. Emergency services were overwhelmed, and reports claim that one man in Valparaíso died of a heart attack from fear.

- 1949, Quito, Ecuador: A dramatized Martian invasion broadcast by Radio Quito incited widespread panic. The program interrupted a live musical performance with simulated news reports of alien landings and a lethal gas cloud approaching the city. Listeners, believing the dramatization was real, panicked. When the station eventually revealed it was fiction, the public felt betrayed—and outrage quickly turned violent. A furious mob set fire to the shared offices of Radio Quito and the newspaper El Comercio, killing at least six people and causing extensive damage. The station was forced off the air for the next two years.

Legacy

The now-legendary War of the Worlds broadcast did more than cause a brief stir—it reshaped the relationship between media and its audience.

It sparked a national conversation about media influence, public trust, and collective psychology. Even decades later, it continues to echo in classrooms, research papers, and pop culture references.

🎙️ In Media Studies:

It’s now required reading (and listening) in journalism, psychology, communications, and media ethics programs. Scholars cite it as one of the earliest examples of “fake news” gone viral, before the internet ever existed.

🎬 In Pop Culture:

From outright parody in The Simpsons to thematic echoes in Network and Don’t Look Up, the 1938 broadcast remains a cultural shorthand for media-induced hysteria and the fine line between entertainment and alarm.

🧠 In Psychology:

The Princeton study helped launch a whole new field exploring how and why people believe what they hear. Today’s research into social media, conspiracy theories, and misinformation traces its roots back to this very event.

📻 In Broadcasting:

The broadcast triggered changes in how simulated news is handled. Modern radio and television now follow strict rules about disclaimers and realism in dramatizations—directly because of this 1938 moment.

As Welles later reflected, he was fed up with how people unquestioningly believed whatever came through “that new magic box”—so he set out to prove just how easily the public could be fooled.

Mission accomplished.

Listen for Yourself

This is the original 1938 Mercury Theatre on the Air performance that changed broadcasting history. Listen with fresh ears—and imagine what it might’ve felt like without any warning. It runs just under an hour and is worth every minute!

Explore more…

Want to see how the broadcast holds up against H.G. Wells’ original novel?

Explore our top resources…

📚 See how it stacks up to our True Adaptations Checklist with our own analysis of the broadcast.

Or, visit our Book Overview and Analysis or Detailed Chapter Summaries to keep exploring The War of the Worlds.

📚 Sources & Further Reading

- American Experience: War of the Worlds. PBS Documentary

- H.G. Wells and the War of the Worlds: A Documentary. Directed by Laurence Holloway. BBC, 2005.

- Gosling, John. Waging The War of the Worlds: A History of the 1938 Radio Broadcast and Resulting Panic – McFarland & Company, 2009. A comprehensive history citing FCC records and contemporary reports, focusing on media exaggeration and regulatory fallout. Available via publisher

- Heyer, Paul. The Medium and the Magician: Orson Welles, the Radio Years, 1934–1952 (2005). A scholarly book detailing Welles’ radio career, providing context on the broadcast’s production and media rivalry.

- Klein, Christopher. ‘The War of the Worlds’ Broadcast: When Americans Thought They Were Under Siege. History, 27 Jan. 2025.

- Meyers, Cynthia B. “The Panic Broadcast of 1938: A Case Study in Media Influence” (2018).

A peer-reviewed study on the broadcast’s role in shaping media ethics and regulation. - Pooley, Jefferson, and Michael J. Socolow. “The Myth of the War of the Worlds Panic” (2013).

A concise, well-researched piece debunking exaggerated panic claims, grounded in historical analysis. - Schwartz, A. Brad. Broadcast Hysteria: Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News – Hill and Wang, 2015. A modern analysis debunking panic myths while affirming localized reactions, using primary sources like listener surveys. Available via publisher

- Trove (Australia): 1944 Chile Panic Coverage – Newspaper archive

- Origins (Ohio State University) – “Orson Welles’s ‘War of the Worlds’” Article

- Orson Welles’s ‘War of the Worlds’ Radio Play Is Broadcast | October 30, 1938. History, 13 Mar. 2025.

- The Infamous ‘War of the Worlds’ Radio Broadcast Was a Magnificent Fluke. Smithsonian Magazine, 6 May 2015.

- This Week in Universal News: The War of the Worlds Broadcast, 1938. The Unwritten Record, National Archives, 27 Oct. 2014.

🎬 Watch the Documentaries

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases. These links are provided for your convenience at no additional cost to you.

Written by AJ – Creator of War of the Worlds Central

Thoughts on the 1938 broadcast or its legacy?

Respectful discussion is welcome — spam, trolling, and hate speech will be vaporized by Martian heat ray.