The War of the Worlds: The Book That Started It All

⚡ Looking for the plot?

Check out our chapter-by-chapter summary for a detailed recap of The War of the Worlds.

Before it was a radio hoax, a blockbuster film, or pop culture shorthand for alien invasion, The War of the Worlds was something far more powerful: a daring experiment in speculative fiction—one that changed the game.

When H.G. Wells wrote it in the late 1890s, he wasn’t just spinning a tale about Martians—he was flipping the script on colonialism and human superiority. His novel broke new ground by imagining Earth as the target—not the conqueror—of an unstoppable colonial force. It forced readers to experience the fear, confusion, and helplessness usually reserved for the “others” of imperial history. It was bold, unsettling, and decades ahead of its time.

More than just an adventure tale, the book challenged the political and scientific assumptions of its day—asking whether humanity truly deserves its place atop the evolutionary ladder.

Estimated reading time: 14 minutes

🖋️ Publication History

By the time Wells wrote The War of the Worlds, he was already making a name for himself with early hits like The Time Machine and The Island of Dr. Moreau.

He was carving out a solid reputation as the go-to voice for bold new “scientific romances.” But he wasn’t famous yet. He was still in his twenties, still broke, and still hustling to make deadlines.

Wells wrote The War of the Worlds between 1895 and 1897 and, like many writers of the day, sold it first as a serial. It ran across nine monthly installments (April–December 1897) in Pearson’s Magazine (UK) and The Cosmopolitan (US).

Not today’s fashion-and-romance Cosmopolitan—this was a very different beast: a general-interest literary magazine with a large and influential readership, perfect for showcasing Wells’ Martian invasion.

Both serials featured moody black-and-white illustrations—not just by Warwick Goble, though he did contribute the majority—but also by Cosmo Rowe.

The American serial edition differed in layout and installment divisions, offering a subtly different pacing and reading experience from the British version.

Additionally, two American newspapers, the New York Evening Journal and the Boston Post, ran unauthorized, rewritten serials under the title Fighters from Mars.

These rewrites appeared from Dec 1897–Jan 1898 (New York Evening Journal) and 1898 (Boston Post), well before the U.S. novel release. They relocated the invasion to American soil and stripped out most of Wells’ social commentary, all without his permission.

Wells was reportedly furious about these unauthorized rewrites, which not only stole his work but also diluted its anti-colonial message. Still, they helped introduce his story to a broader American audience, paving the way for its lasting popularity.

In March 1898, the complete novel was published in hardcover by William Heinemann in London, achieving strong sales in its first five years, with thousands of copies sold. It was translated into ten languages by 1903, a further testament to its success. Unlike the serial versions, the novel was published without illustrations. It’s never gone out of print.

⚖️ Justice for Cosmo!

While Warwick Goble often gets all the credit for illustrating The War of the Worlds serials, he wasn’t the only artist bringing Martians to life in 1897. Cosmo Rowe, an American illustrator and friend of Wells, contributed two early illustrations that appeared in both the UK and U.S. serializations—though rarely with credit.

Rowe, a lesser-known artist than Goble, brought a gritty realism to his two illustrations, contrasting Goble’s more decorative, stylized approach.

Rowe’s work was quickly overshadowed. He didn’t receive the same byline attention as Goble, and his quieter career meant he gradually faded from view—first eclipsed by Goble’s distinctive visuals, then later by Henrique Alvim Corrêa’s famously intense 1906 illustrations.

It’s a small role—but a real one. And after more than a century in the margins, it’s about time Cosmo got some love.

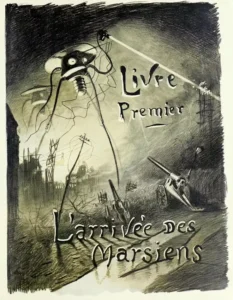

While Rowe and Goble helped define the earliest visual take on Wells’ Martians in the 1897 serial versions, the dramatic illustration featured at the top of this page comes from a now-iconic 1906 Belgian edition of The War of the Worlds, illustrated by Henrique Alvim Corrêa.

Known for its dark intensity and fine detail, Corrêa’s work earned high praise from Wells himself, who said the artist had “done more for my work with his brush than I with my pen.”

Timeline: The War of the Worlds – From Draft to Classic

- 1895–1897

✍️ Wells writes The War of the Worlds after the success of The Time Machine. - April–Dec 1897

🗞️ Serialized in Pearson’s Magazine (UK) and Cosmopolitan (US). - 1898

📘 Published as a hardcover novel by William Heinemann in London. - 1898

🚨 Unauthorized serials (Fighters from Mars) appear in New York and Boston newspapers. - 1903

🌍 Translated into ten languages and firmly established as a science fiction landmark.

✂️ From Serial to Novel: Editing Under Pressure

The War of the Worlds wasn’t born as a polished novel—it evolved. Like many writers of his day, Wells sold the story first as a serial. Writing for Pearson’s Magazine meant breaking it into 9 tight, suspenseful installments, each one ending with just enough tension to hook readers into the next.

That format came with constraints: limited word counts, monthly deadlines, and a need to keep the action moving. The result was a fast-paced, episodic structure that leaned into cliffhangers and momentum. It worked for the magazine crowd, but Wells had more on his mind.

When the full novel was published in 1898, Wells likely took the opportunity to revise—smoothing out transitions, tightening the language, and bringing his deeper themes into sharper focus.

The abrupt stops and restarts of serialization gave way to a more fluid structure. The story now unfolded in two larger arcs—Book I: The Coming of the Martians and Book II: The Earth Under the Martians—stretched across 27 chapters.

Wells biographer Peter J. Beck points out that the shift from serial to novel format allowed Wells to “sharpen his ideas—and push his message further,” transforming the story from fast-paced entertainment into a potent work of social critique.

The revisions created space for deeper reflection, especially on themes like colonialism, evolution, and the fragility of human society. That balance of scientific plausibility and social commentary helped set the book apart.

What began as serialized suspense grew into a fully realized social critique, dressed up in tripod legs and black smoke.

“He was writing against the grain of his culture, with a subversive message wrapped in scientific spectacle.”

— Peter J. Beck, The War of the Worlds: From H.G. Wells to Orson Welles (2016)

One luxury Wells didn’t have? Control over those pirated versions that popped up in American newspapers. These knockoffs were clumsy rewrites that missed the point entirely. Thankfully, the real version—Martians, microbes, metaphors and all—survived.

📊 Serial vs. Novel Comparison Box

Click the arrow to reveal details…

Serial: Episodic, cliffhangers, illustrated

📖 Serial Version (1897)

- Published in monthly installments

- Cliffhangers at the end of each part

- More abrupt pacing

- Warwick Goble (and Cosmo Rowe) illustrations

- Written quickly under deadline pressure

Novel: Seamless narrative, expanded detail, unified themes

📘 Novel Version (1898)

- Revised into two “books”

- Smoother narrative transitions

- Expanded themes and descriptions

- No illustrations in first edition

- Unified vision and more polished prose

🧠 What It All Means: Themes in The War of the Worlds

Wells wasn’t just telling a sci-fi story—he was holding up a mirror to the world. Beneath the tripods and Heat-Rays, The War of the Worlds is a sharp, unsettling critique of Victorian society, science, and human behavior.

🌍 Colonialism in Reverse

In the late 1800s, Britain was busy colonizing huge swaths of the globe. Wells flipped the perspective: what if it was us on the receiving end? The Martians treat humans the way imperial powers treated Indigenous peoples—ruthlessly, efficiently, and without remorse. It’s no accident that Wells references the extermination of the Tasmanian Aboriginals.

“And before we judge of them too harshly, we must remember what ruthless and utter destruction our own species has wrought… The Tasmanians, in spite of their human likeness, were entirely swept out of existence… Are we such apostles of mercy as to complain if the Martians warred in the same spirit?”

— Narrator (musing in Chapter 1: The Eve of the War)

Wells challenges the Victorian notion of human supremacy, reminding us that life on Earth isn’t guaranteed. His Martians, cold and calculating, are as much a mirror to human imperialism as they are a terrifying otherworldly force.

🧬 Evolution and Natural Selection

Wells studied under T.H. Huxley, Darwin’s fierce advocate known as ‘Darwin’s bulldog,’ and it shows. The Martians are intellectually superior and more technologically advanced. But in the end, they fall to Earth’s simplest lifeforms: bacteria. Nature—not humanity—wins.

“By the toll of a billion deaths man has bought his birthright of the earth, and it is his against all comers… because in all the universe he had no competitor.”

— Narrator (reflecting on Martian’s biological defeat)

This outcome reflects Wells’ grounding in Darwinian theory, showing how even the most advanced beings are subject to natural law (Crossley, 1986; Hughes & Geduld, 1998).

🧘♂️ Arrogance and Human Fragility

The War of the Worlds is more than a tale of survival. It’s a profound exploration of humanity’s hubris and vulnerability.

“What is courage, and what is cowardice? Was it courage to lie on the floor as I did, or was it cowardice?”

— Narrator (after hiding from the Martians)

For all our pride and progress, the novel shows just how thin the veneer of civilization really is. Governments collapse, crowds panic, and individuals snap under pressure. The narrator’s own mental state begins to unravel, mirroring the chaos around him.

🔥 Technology Without Morality

The Martians are the ultimate cautionary tale about tech without ethics. They possess incredible machines, but no empathy. Wells seems to ask: what good is progress if it’s used only to dominate and destroy?

“No one would have believed… that this world was being watched keenly and closely by intelligences greater than man’s and yet as mortal as his own.”

— Opening line (and one of the most iconic in sci-fi history)

🙏 Religion vs. Reality

Wells doesn’t hold back in his criticism of organized religion. Through characters like the curate—who descends into useless hysteria— the novel questions whether blind faith offers any real answers in the face of existential threat (Parrinder, 1995).

“Be a man!… What good is religion if it collapses under calamity? Think of what earthquakes and floods, wars and volcanoes, have done before to men! Did you think that God had exempted [us]? He is not an insurance agent.”

— The Narrator to the Curate

The curate’s descent into madness contrasts sharply with the narrator’s pragmatic survival instincts, reflecting Wells’ skepticism of religion’s ability to address real-world crises.

🚀 Legacy and Influence

The War of the Worlds didn’t just launch a thousand adaptations—it helped define what science fiction could be. Wells took Victorian fears and curiosities and turned them into something that still hits home more than a century later.

📚 A Blueprint for Sci-Fi

Wells’ Martian invasion became the prototype for alien encounter stories across books, films, and TV. From Ray Bradbury to Octavia Butler, generations of writers have drawn on Wells’ ideas. Modern works like Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem echo Wells’ themes of extraterrestrial contact and human vulnerability.

📻 The Panic Broadcast

In 1938, Orson Welles’ infamous radio adaptation convinced some American listeners that the Martians had actually landed. The scale of the panic is often exaggerated, but the cultural impact is real. It proved this story could still scare people—especially when dressed up as breaking news.

🎬 From Tripods to Technicolor

From the 1953 Technicolor film to Spielberg’s 2005 blockbuster, The War of the Worlds has been reimagined for every generation. It inspired a prog rock concept album, countless comics, multiple TV series, and more spin-offs than Wells could have imagined. You don’t need tripods to recognize its DNA in everything from The Day the Earth Stood Still to Independence Day.

🧪 Real-World Ripples

The novel didn’t just shape fiction—it sparked scientific ambition. Rocket pioneer Robert H. Goddard credited The War of the Worlds with inspiring his interest in space travel.

The story also significantly contributed to a shift in science fiction. It amplified the genre’s speculative potential, pushing it further from pulp adventure toward a place where science, ethics, and imagination powerfully collide.

🧠 Still Taught, Still Relevant

Today, the novel is standard reading in schools and universities around the world. It’s studied not just for its historical context, but for the way it blends action, allegory, and big ideas.

“More than a period piece, The War of the Worlds continues to resonate because of its capacity to be read in new ways by each generation.”

— Peter J. Beck, From H.G. Wells to Orson Welles (2016)

In an era of AI advancements and climate crises, Wells’ warnings about unchecked technology and humanity’s vulnerability to nature’s smallest forces feel as pertinent as ever.

The fact that it’s still in print—and still unsettling—is a true testament to its staying power.

🎬 War of the Worlds in Pop Culture

A few highlights from over a century of Martian mayhem:

- 1898 – 📘 Novel published in London

- 1938 – 📻 Orson Welles’ radio drama causes public panic

- 1953 – 🎞️ George Pal’s Technicolor film sets the standard for alien invasion movies

- 1978 – 🎶 Jeff Wayne’s prog rock musical hits UK charts

- 2005 – 🎥 Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster reimagines the invasion with post-9/11 themes

- 2019 – 📺 BBC miniseries returns to Victorian roots

Martians have been invading pop culture for over a century—and they’re not done yet.

Dive into the full scope of War of the Worlds adaptations, from faithful recreations to the truly bizarre.

📖 Click for a Quick Plot Summary

Mysterious explosions on Mars signal the start of something far more terrifying: an alien invasion. Cylindrical spacecraft crash into the English countryside, unleashing towering tripods equipped with deadly Heat-Rays and poisonous Black Smoke. As cities fall and panic spreads, human resistance proves useless against the Martians’ advanced technology.

An unnamed narrator recounts his desperate attempt to survive—and to reunite with his wife—amid the chaos. Along the way, he crosses paths with a fanatical curate, a delusional artilleryman, and scenes of devastation that shake his faith in science, society, and human nature. Meanwhile, his brother’s journey across London shows the broader collapse of civilization from a different angle.

In the end, it’s not human ingenuity that saves Earth—it’s nature. The Martians are brought down by Earth’s smallest lifeforms: bacteria. The invasion ends not with a heroic stand, but with the quiet collapse of immune systems that never saw it coming.

The War of the Worlds is more than a classic. It’s a lens through which we can explore fear, arrogance, and the resilience of the human spirit. This book isn’t just about aliens and destruction; it’s about survival, perspective, and the reminder that we are not invincible. And that’s a lesson that never gets old.

If this is your first time delving into Wells’ world, you’re in for an unforgettable ride. For returning readers, it’s always worth revisiting its haunting beauty, layered meaning, and timeless warnings. Either way, I hope this breakdown of the chapters, adaptations, and themes enhances your appreciation for one of the greatest sci-fi novels of all time.

📘 Want to own the book?

Buy The War of the Worlds on AmazonDisclosure: As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.

👀 Keep Exploring

- 🔍 Detailed Chapter Summaries »

- 🎧 That Notorious Broadcast: 1938 Panic »

- 🎬 List of Notable Adaptations »

- ✅ True Adaptations Checklist & Reviews »

📚 Sources & Further Reading

- Compare the 1897 serializations at The (De)collected War of the Worlds for facsimiles and insights into Cosmopolitan and Pearson’s Magazine editions.

- Beck, P. J. (2016). The War of the Worlds: From H.G. Wells to Orson Welles. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Cantril, H. (1940). The invasion from Mars: A study in the psychology of panic. Princeton University Press.

- Clary, D. A. (2003). Rocket man: Robert H. Goddard and the birth of the space age. Hyperion.

- Crossley, R. (1986). H.G. Wells, The War of the Worlds, and the invasion narrative. Science Fiction Studies, 13(3), 277–288.

- Gosling, J. (2009). Waging The War of the Worlds: A history of the 1898 novel and its legacy. McFarland & Company.

- Haynes, R. D. (1980). H.G. Wells: Discoverer of the future. Macmillan.

- Hughes, D. Y., & Geduld, H. M. (Eds.). (1998). A critical edition of The War of the Worlds: H.G. Wells’s scientific romance. Indiana University Press.

- Huntingdon, J. (1995). The science fiction of H.G. Wells. In The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction (pp. 34–47). Cambridge University Press.

- James, S. (2012). H.G. Wells and the evolutionary imagination. Victorian Literature and Culture, 40(1), 227–243.

- McLean, S. (2009). The early fiction of H.G. Wells: Fantasies of science. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Parrinder, P. (1995). Shadows of the future: H.G. Wells, science fiction, and prophecy. Syracuse University Press.

- Parrinder, P. (2005). H.G. Wells: The critical heritage. Routledge.

- Rieder, J. (2008). Colonialism and the emergence of science fiction. Wesleyan University Press.

- Roberts, A. (2006). The history of science fiction. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schwartz, A. B. (2015). Broadcast hysteria: Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds and the art of fake news. Hill and Wang.

- Seed, D. (Ed.). (2012). A companion to science fiction. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Wells, H. G. (1898). The War of the Worlds. William Heinemann.

- Westfahl, G. (2000). Science fiction and the prediction of the future. McFarland & Company.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. The War of the Worlds (novel by Wells). britannica.com.

- Explore the H.G. Wells Society for resources, events, and updates on Wells’ life and works.

- Discover more about Wells at the Literature Network’s H.G. Wells page for biography, works, and resources.

- Read The War of the Worlds free on Project Gutenberg, the full text of the classic novel.

- Check out the Science Fiction Studies’ archived articles at DePauw University for historical research and scholarship on Wells.

- Visit the new Science Fiction Studies site, published by the University of California Press, for current issues and the latest Wells scholarship.